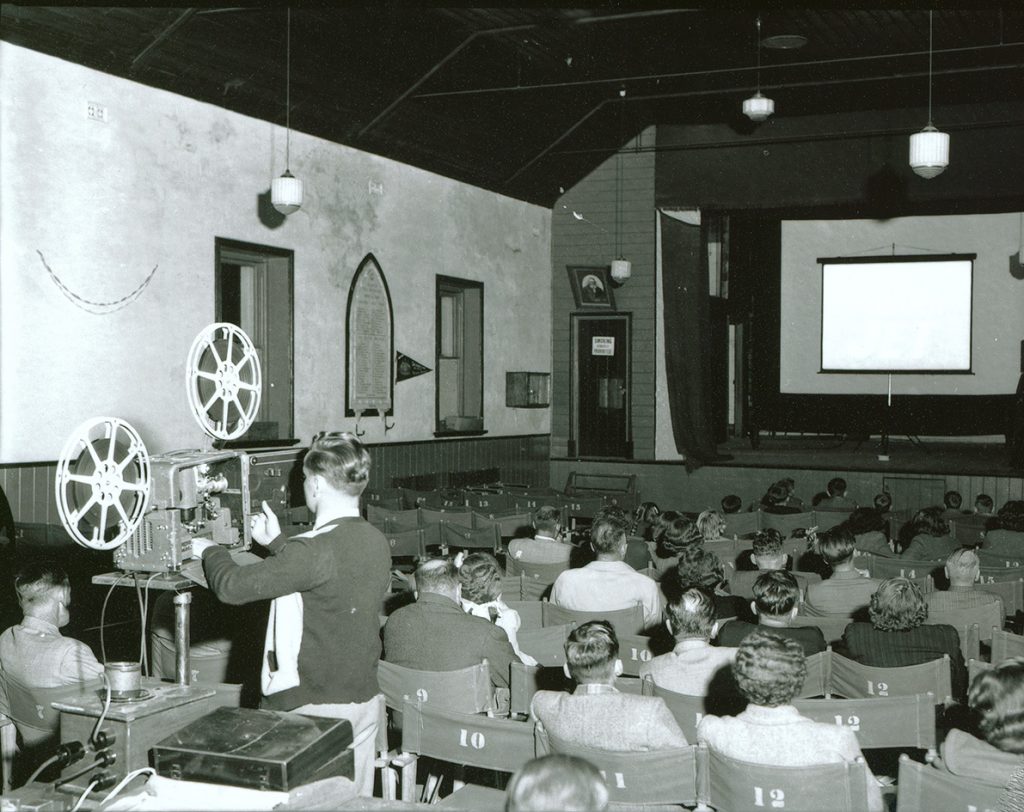

The 1940s was a crucial time for Australian documentary. In 1940, John Grierson, the reputed “father of British documentary” visited Australia and extolled the importance of the genre for nation building. Government sponsored documentary was a key media form. It was supported by institutions such as the Film Division of the Department of Information and later the Australian National Film Board. Far from simple propaganda or educational films, the film units of the time created a vibrant documentary culture in Australia.

Documentary was also part of the geopolitics of imperialism. It contributed to a broader context in which, from the 1920s, cinema was deployed by corporate entities and governments (and partnerships between the two) in order to further global capitalism in a range of locations and modalities. This contributed to the consistent take up of documentary by oil companies in the 20th century. The public relations agenda of oil companies has recognised the potential of moving image culture in sophisticated ways, going beyond predictable advertising forms to more comprehensively, as Mona Damluji observes, “seamlessly equate the story of oil with the experience of modernity”.

This study explores the work of Royal Dutch Shell in the postwar era, especially the operation of the Shell Film Unit Australia (SFUA), exploring how petrofilm connected petroleum culture, documentary film culture and ways of perceiving the nonhuman environment.

Publication

Smaill, Belinda. “Petromodernity, the Environment and Historical Film Culture.” Screen. 62.1 (2021): 59-77.

This article investigates the history of production, distribution and documentary representation within the sphere of the Shell Film Unit Australia. It examines how the mobile film units deployed in the Australian outback offer a way of considering the conjunction of environment and film practice. It also attends to the SFUA’s production schedule with close analysis of both prestige documentary and explicitly promotional, utilitarian film. The analysis focuses on two very different films, The Forerunner (John Heyer, 1958) and Let’s Go (John Heyer, 1956) , examples that are compelling because they provide two distinct ways of understanding the natural environment. As popular cultural artefacts, these films were produced and circulated to both fulfil the SFUA agenda and appeal to audiences of the period. They show us the cultural imagination of the time and how it was shaped in ways that histories of science and policy pertaining to the environment cannot.

Quotes

“While there have been important studies of the film practices of, in particular, Shell and British Petroleum, almost none have undertaken detailed critical studies of the relationship between popular knowledge about the natural environment and what I refer to as petrofilm culture (or the institutions, films, personnel and distribution of film produced by oil companies).”

“The moment before the environment takes hold as an idea is also a moment when companies such as Shell were willing to provide film units both with funds and creative freedom. In the two film examples I have discussed, it is possible to perceive how film practitioners in Australia interpreted Shell’s agenda in ways that also aligned with their own cinematic aspirations”

“The SFUA films, beyond a preoccupation with a generic outback vista, do not provide a consistent catalogue of iconography, whether species or landscapes. This may be because the primary audience was a domestic one who needed to be convinced that Shell was “with them,” rather than an international audience who likely would have been appeased by familiar tropes.”

Key Films

The Forerunner (1957)

Let’s Go (1956)

The Back of Beyond (1954)